Most of the medical malpractice cases Miller & Zois handles come from cases that are referred from other Maryland attorneys. These cases come from other lawyers who do not focus their practice on medical malpractice cases, or the size and the expenses in the case or the specific issues presented are such that getting other counsel involved makes the most sense.

Most of the medical malpractice cases Miller & Zois handles come from cases that are referred from other Maryland attorneys. These cases come from other lawyers who do not focus their practice on medical malpractice cases, or the size and the expenses in the case or the specific issues presented are such that getting other counsel involved makes the most sense.

What Type of Referring Lawyer Fee Splits Do You Do?

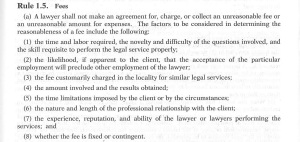

In these cases, we do a 70%-30% fee split with the referring law consistent with Maryland Rule 1.5 in medical negligence cases. Our firm fronts and bears the risk of all costs and expenses. I put that 70%-30% number right out there because fee splits always seem cloaked in mystery. The only information online that involves fee splits comes from appellate opinions. So we want to get it out there.

How Does It Work When an Attorney Refers a Case?

How our referral process works depends upon the referring lawyer. There are lawyers that send us cases in bulk that really do not care to be involved in the case. In these cases, we provide status reports of key developments but otherwise take the ball and run with it without a great deal of consultation. This is perfectly acceptable under the Maryland Rules. A division of fees between attorneys not in the same law firm can be made without consideration of how much work is being done as long as the fee arrangement is in writing, each lawyer assumes joint responsibility for the claim, and the client is fully on board. Other referring attorneys want to stay involved in the case. Often, they have some personal connection with the client and want to be a part of the process and want the client to feel like the lawyer has not abandoned them. We are sensitive to this. Usually, the referring lawyer comes out of it looking pretty good with the client. They are giving up some portion of their fee so that the client can get the best possible joint legal team without it costing them an extra penny.

Referral Fees

Lawyers often refer to fee-splitting as referral fees. I do not think referral fees is the right word. “Referral fee” sounds like you are getting a fee just for referring the case. Under Maryland Rule 1.5, you cannot get a fee just for referring someone a case. The referring lawyer is co-counsel and technically shares joint responsibility for the case, even if our firm is doing all the work. This means you need to be confident that the law firm you are referring the case to will not commit legal malpractice and has adequate insurance coverage.

Why Is Our Referral System Is a Good System for the Public?

Let’s say there was a rule that lawyers could not get other attorneys involved while retaining a portion of the fee. What would that incentivize lawyers to do? Take cases they do not have the skills, resources, or time to handle. This is a disaster for victims. Instead, we have a rule that allows victims to have the very best medical malpractice lawyers, even if the victim didn’t initially hire them. That is a good system.

Pending Maryland Court of Special Appeals Case

There is a case pending before the Maryland Court of Appeals where the parties were not so lucky. A lawyer who does not handle malpractice claims had a mother-in-law who was allegedly negligently hurt during surgery. The family was split on bringing a malpractice claim. The lawyer goes to a sporting event and meets the name partner of a law firm — a very good law firm — who told the referring lawyer that his firm handles medical malpractice claims in Maryland.

So far everything is working like it should, right? A lawyer not suited to handle the case refers the claim to a law firm with a great history of getting quality verdicts and settlements in medical malpractice cases. Allegedly, a “referral fee” was discussed at the sporting event and later confirmed. One thing is not in dispute. The fee agreement was not in writing.

The referring lawyer files suit. The trial court found for the malpractice attorney. What I’m sure was decisive is that in a he said/she said disagreement, you have to wonder why there would be no written agreement. Did he really believe that the 30% number was so clear that it did not have to be in writing? Was he concerned that the Maryland Rules require that there be notice to the client and approval of the fee split and that good sense would involve notifying the client in writing of this fact on the fee agreement (which we always do). Also of interest is that the law firm does not do 30% fee splits (which is what we do). So the number 30% may have seemed to the court to underscore that the referring lawyer simply misunderstood the deal.

What actually happened here? No one knows except for the parties involved and they might even in good faith remember it wrong. The best argument going for the referring lawyer is why wouldn’t he have gotten a fee split if the law firm has a history of doing fee splits on medical malpractice cases? There are several possible answers. The one that comes to mind to me is that maybe the firm would not have taken the case with a fee split. Sure, in hindsight, it was a pretty good case, fetching over a million dollars. But we have gotten seven-figure results in cases that we would not have taken if there was a fee split involved. So maybe one was not offered. Alternatively, maybe the referring lawyer just never asked. The whole mess is compounded by the client not wanting the referring lawyer to get any money. It really puts the malpractice lawyer between a rock and a hard place.

One thing is for sure. Both the referring lawyer and the malpractice attorney screwed up by not setting out the expectations one way or the other in writing from the very beginning.

More Information

- Maryland ethical rule on fee sharing

- Another Maryland appellate case with a dispute between referring lawyers

- More on referring your case to Miller & Zois

Maryland Injury Law Center

Maryland Injury Law Center